- 21.1 The Extinguishment Rules – Introduction

- 21.2 Table Summarising the Extinguishment Rules by Class of Collateral

- 21.3 The Extinguishment Rules - Commentary

- 21.4 Buyer or lessee of personal property subject to unperfected security interests – section 43

- 21.5 Sales or leases of serial-numbered property – motor vehicles, watercraft, aircraft/engines and intellectual property (patents, trade marks, designs and plant breeder’s rights) – section 44

- 21.6 Private sales or leases of motor vehicles – sections 45(1) - (2)

- 21.7 Buying motor vehicles from licensed dealers – sections 45(3) - (4)

- 21.8 Buying or leasing from a seller/lessor in the ordinary course of business – section 46

- 21.9 Low value (below $5,000) consumer property (except serial numbered property) – section 47

- 21.10 Currency – section 48

- 21.11 Prescribed financial markets – investment instruments and intermediated securities – section 49

- 21.12 Investment instruments – section 50

- 21.13 Intermediated securities – section 51

- 21.14 Temporarily perfected security interests – section 52

- 21.15 Returned goods following sale or lease

- 21.16 Subrogation by extinguished secured parties to rights in relation to collateral sold or leased

The PPSA provides for around ten (10) (depending on how you count them) extinguishment rules under which security interests can be extinguished when the grantor sells or leases collateral covered by a security interest. Some level of protection is required for buyers and lessees of personal property to facilitate commerce and the workings of Australia’s market economy in which people regularly buy, sell and lease personal property.

The extinguishment rules aim to strike a balance between protecting secured parties when collateral is transferred without their consent to others, and protecting those who buy or lease collateral from a grantor.

The extinguishment rules have many conditions to their operation. It is completely conceivable that in various instances buyers and lessees will not be protected, and that security interests will continue unextinguished in collateral when transferred or leased.

The Table in Section 21.2 lists the key features of each of the ten (10) extinguishment rules.

The background, policy and a few matters relating to the extinguishment rules are discussed before approaching the table. Hopefully this makes the Table in Section 21.2 easier to understand.

Following the Table in Section 21.2, each extinguishment rule is discussed separately in more detail.

What security interests do the extinguishment rules “extinguish”

Some points to note at the outset about the Table in Section 21.2 below and the extinguishment rules in general are that:

(a) most extinguishment rules operate to extinguish “any” security interests over collateral sold or leased, not just security interests granted by the immediate seller or lessor; and

(b) some extinguishment rules extinguish only certain security interests, being:

(i) the extinguishment rule in section 46 (sale or lease in the ordinary course of business), which is restricted in application to where the immediate seller or lessor is the person who granted the security interest to be extinguished; and

(ii) the extinguishment rule relating to the private sale of motor vehicles (section 45(1)), which is restricted in application to where either:

(A) the immediate seller or lessor is the person who granted the security interest to be extinguished; or

(B) a person in possession of the motor vehicle sells or leases it and the person who granted the security interest over the motor vehicle has lost the right to possess the motor vehicle, or is estopped from asserting an interest in the motor vehicle. This appears (it is unclear) to capture the situation where a lessee of a motor vehicle purports to sell it.

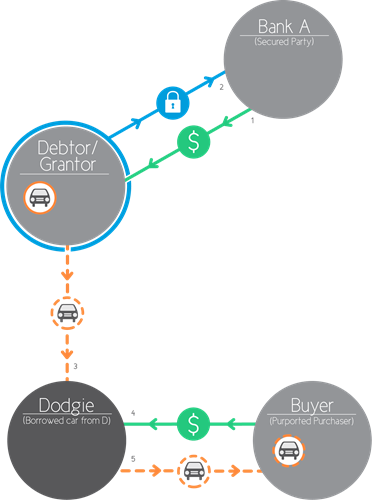

This raises the question of the relationship between the extinguishment rules and the general law principle of nemo dat quod non habet (no one can give what he does not have). Do the extinguishment rules apply to extinguish a security interest for the benefit of a buyer or lessee where the seller or lessor is not the person who granted the security interest? Diagram 9 below illustrates this situation.

Diagram 9

![]()

1. Loan

2. Security interest over all present and after-acquired property

3. Loan of car to Dodgie

4. Sale (purported) of car to Buyer

5. Transfer of (possession of) car to Buyer

In the above diagram, the debtor/grantor D grants a security interest over all its assets including a motor

vehicle to Bank A in return for a loan. Bank A registers the security interest against the serial number of the car. Assume that Dodgie borrows the car from D. Assume next that Dodgie tries to sell the car to B, but B does not search the PPS Register against the serial number of the car (which would have revealed Bank A’s security interest). As discussed below, B buys the car subject to Bank A’s security interest (Bank A’s security interest is not extinguished).

From the language of the extinguishment rules, the extinguishment rules appear merely to extinguish security interests for the benefit of purchasers or lessees. They say nothing at all about whether title to the collateral being transferred is validly passed to buyers. This point is developed below.

What is nemo dat?

The principle of nemo dat provides that a seller or other party cannot assign to another title or an interest in property that he himself does not have. Take for example section 27 of the Goods Act 1958 (Vic) and equivalent provisions in the sale of goods legislation in other Australian States. These provisions provide that the general rule is that a person who purports to sell goods but who has no title to them, cannot deliver any title to a buyer. This is a codification of the nemo dat principle in relation to the sale of goods. The sale is a nothing, unless one of the exceptions to the nemo dat principle applies.

There are certain exceptions to the nemo dat principle, most of which relate to non-owners selling as agents of the true owner and authorised to bind the seller to the sale. There are other exceptions to nemo dat under the sale of goods legislation in Australia's various States. For example, in some States such as Western Australia, bona fide purchasers of goods for value without notice in "market overt" (a recognised and regularly held market) can take good title to goods even if the seller does not have good title (because, for example, the goods are borrowed or stolen)1. The market overt exception to the nemo dat principle has been abolished in England, and certain other Australian States such as New South Wales and Victoria.

Another exception to the nemo dat principle is that a seller of goods who remains in possession of the goods after the goods have been sold and title transferred to a buyer, can re-sell and give good title to another buyer who acts in good faith and has no notice of the previous sale2. The justification for this exception to nemo dat is that the seller looks like the owner while the seller remains in possession of the goods. This is another manifestation of the apparent ownership problem – see Chapter 15 (Why the PPSA)) for discussion.

The PPSA extinguishment rules and the nemo dat principle

While this does not appear from the language of the extinguishment rules or any other provision in the PPSA, most commentators point to the general "scheme" of the PPSA to support an interpretation that the grantor under a security interest (possibly even grantors that do not have title such as lessees, consignees, bailees or buyers under conditional sales) can dispose of (lease or sell, depending on the circumstances) the collateral and the extinguishment rules may apply to the sale or lease.

A lessee granting a sublease is one thing, but a lessee actually selling title is quite another. To be honest, the author's initial view on reading the PPSA was that a grantor without title could sublease (or similar) but not

sell collateral, and that the nemo dat principle would still apply to provide that a grantor without title could not sell, in which case the extinguishment rules would not operate. The author acknowledges the views of other commentators, and agrees that it is arguable that the "scheme" of the PPSA may permit a mere "possessory" grantor to (sub)lease and extinguish security interests, however, the purported sale of collateral by a lessee (or other "possessory grantor") to extinguish security interests is clearly more difficult.

The absence of clear language on this important aspect is interesting. The United States and Canadian cases discussed below may inform this issue.

Assume for the moment that the "scheme" of the PPSA enables grantors without title to sell collateral and extinguish security interests — the PPSA extinguishment rules would then do much more than simply apply to the matter of whether buyers or lessees take free of existing security interests over the collateral in otherwise valid sales or leases. Rather, the extinguishment rules would then go further and deliver title to a buyer or lessee which

(i) a seller or lessor did not have themselves, or

(ii) where the sale or lease is not validly completed,

although see the discussion below (commencing at paragraph 21.1.18) about the application of the extinguishment rules to agreements to sell and lease.

The issue can perhaps be stated in the following question - is the passage of title and assignment of interests

(not security interests) a matter for the general law of assignment and nemo dat only, or matters also for secured transactions law? Clearly there is overlap where a grantor sells or leases collateral.

United States, Canadian and New Zealand case law on the extinguishment rules

Canadian and United States cases have considered the operation of the extinguishment rules under the Canadian and United States equivalents to the Australian PPSA, usually in the context of the sale of goods. For simplicity the discussion below is limited to sales, not leases, though the extinguishment rules apply equally to sales and leases.

The United States and Canadian case law is consistent that there must first be a valid sale for the extinguishment rules to apply. The extinguishment rules clearly apply where a grantor sells collateral. The most common issue is what “sale” means – is an agreement to sell enough, or must title pass?

Disputes seem to have been most common in the United States, Canada and New Zealand where goods are being manufactured (for instance, ships or motor vehicles), or remain unascertained (in bulk, for example, wheat in a silo), and the manufacturer or seller has granted an all-assets security interest that attaches to the seller's or manufacturer's interest in the unfinished or bulk goods3.

In sales of unascertained (unfinished) goods or bulk goods, depending on the applicable sale of goods legislation, title may not pass until the goods under manufacture are completed (ascertained) and allocated (appropriated) to the sale, or bulk goods are separated from the bulk and allocated (appropriated) to the sale. The problem arises where the seller or manufacturer enters into bankruptcy, administration or liquidation before the completion of goods under manufacture, or the separation of bulk goods. If a buyer has paid in full or in part for the goods, the buyer may end up in a dispute with a secured party holding a perfected (often all-assets) security interest. The secured party typically argues that the buyer takes no title and the unfinished or bulk goods remain the property of the grantor and subject to the security interest.

Cases that hold or support the view that title must first pass to the buyer for there to be a sale to which the extinguishment rules will apply

Perhaps the leading and strongest authority in favour of the view that title must first pass in a sale for relevant extinguishment rules under the PPSA to apply to the sale is the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal decision in Royal Bank of Canada v 216200 Alberta Ltd4 (Alberta).

Alberta involved a furniture retailer who had granted a perfected all-assets security interest to Royal Bank of Canada (RBC). Upon the appointment of receivers by RBC to the assets of the retailer, disputes arose with various classes of purchasers of furniture, many of whom had ordered furniture through the retailer and paid in full or part. The retailer had not itself taken delivery of the furniture from wholesalers, and accordingly, there was no appropriation of the furniture to any sales to buyers.

The court in Alberta confirmed that there must be a sale of goods for the purposes of the relevant sale of goods legislation before any question of the application of the extinguishment rules to the sale arises. The court held that a sale under the Saskatchewan Sale of Goods Act requires the passage of title to the buyer, which does not occur until the goods to be sold are appropriated to the sale5. Accordingly, the buyers of furniture were mere unsecured creditors of the furniture retailer, the retailer itself not having acquired the furniture and there being no appropriation of the furniture to customer purchases. There were no “sales” to which the extinguishment rules could apply to extinguish RBC’s security interest over the furniture. RBC prevailed over the furniture.

The court in Alberta referred to the competing lines of authority in the United States, and preferred the Wisconsin Supreme Court decision in Chrysler Corp v Adamatic Inc. (1973) 208 N.W. (2d) 97 (Chrysler). Chrysler held that an agreement to sell, and a sale, are different things. Accordingly, only an actual sale by which title to property passed would attract the extinguishment rules under Article 9 of the United States Uniform Commercial Code (the equivalent United States legislation to the Australian PPSA) as adopted in Wisconsin. The contrary line of authority in the United States, which holds that the extinguishment rules apply to mere agreements to sell, is the Illinois Appellate Court decision in Herman v First Farmers’ State Bank of Minier (1979) 392 N.E. 2d 344, and another Supreme Court of Wisconsin decision in Daniel v Bank of Hayward (1988) 425 N.W. 2d 416.

The British Columbia Supreme Court recently (in 2002) followed Alberta in Re Anderson’s Engineering

Ltd6 (Anderson). After referring to a contrary line of authority from the Ontario Court of Appeal in Spittlehouse v Northshore Marine Inc. (Spittlehouse), which is discussed below, the court in Anderson preferred the view that property in goods must have passed to a buyer in accordance with the applicable sale of goods legislation before there can be any application of a PPSA extinguishment rule to extinguish security interests over the goods sold for the benefit of a purchaser7.

Cases that hold or support the view that an agreement to sell (without passage of title) is sufficient for the application of the extinguishment rules

The leading Canadian case that supports this line of authority is the Ontario Court of Appeal decision in Spittlehouse v Northshore Marine Inc. (Spittlehouse). In Spittlehouse, a boat manufacturer (Northshore Marine) agreed to build a boat for a purchaser (Spittlehouse). Northshore Marine accepted 90% of the purchase price upfront, and the remaining 10% was due on completion and delivery of the boat. The boat sale contract provided that title to the boat would remain with the manufacturer/ seller until payment was made in full. Northshore Marine had granted a perfected all-assets security interest over its assets (which included the boat under construction) to Transamerica Commercial Finance (Transamerica).

Transamerica appointed a receiver to Northshore Marine following a default, and naturally argued that its perfected security interest attached to the boat under construction, and that title to the boat had not passed to the buyer Spittlehouse. Transamerica’s argument continued that the extinguishment rules did not apply to extinguish Transamerica’s security interest in the boat.

The court in Spittlehouse held that the extinguishment rules under the Ontario PPSA apply even to agreements to sell, even where title has not yet passed from the seller to the buyer8. This meant that the interest of the buyer of the boat, Spittlehouse, defeated Transamerica’s security interest. The court emphasised that the spirit of the PPSA is to avoid technical rules about when title passes, and is to look to the substance of transactions. Spittlehouse does not, however, override the nemo dat principle, as discussed at paragraphs 21.1.34 and 21.1.35 below.

Closer to home, the High Court of New Zealand seems to have gone even further in Orix New Zealand Limited v Milne & Nicholls9 (Orix).

In Orix, Orix New Zealand lent money to Comquip to finance Comquip’s purchase of marini paving machines. Comquip granted a perfected security interest over the paving machines to Orix. In a group reorganisation, Comquip transferred title to one particular paving machine to a related company, Pavement. Pavement sold this paving machine to Nicholls, and a dispute developed between Nicholls and Orix. Nicholls argued that the “sale in the ordinary course of business” extinguishment rule applied to the sale of the paving machine by Pavement to Nicholls and extinguished Orix’s security interest in the paving machine.

Orix, holding a perfected security interest over the paving machine (albeit granted by the previous owner, Comquip, not the most recent seller, Pavement), argued that the “sale in the ordinary course of business” extinguishment rule applies only to extinguish security interests granted by the immediate seller (which is consistent also with the language of the equivalent provision under the Australian PPSA, section 46). Orix argued that a sale by Pavement could not extinguish a security interest granted by Comquip. Put another way, Orix argued that its security interest in the paving machines could not be extinguished by the sale by Pavement to Nicholls because the grantor of the security interest to Orix was the previous owner, Comquip.

The New Zealand High Court seems to have held that a non-owner can sell goods and pass title to a buyer. The court held that Comquip (a non-owner, having transferred the paving machine to Pavement) somehow managed to be the seller of the paving machine to Nicholls, despite the evidence showing that Pavement owned the paving machine, and sold it to Nicholls. The court was clearly striving to protect the buyer by fitting the situation within the applicable extinguishment rule, which only extinguishes security interests granted by the immediate seller.

Agreements to sell are not sales without title

Even if the extinguishment rules apply to agreements to sell (future or unascertained property), this does not necessarily mean that the extinguishment rules apply to purported sales by persons without any title or right to sell at all. The United States and Canadian cases involve (for the most part) the sale of uncompleted goods, not goods to which the seller had no title or right to sell at all.

There appears to be no suggestion in the United States or Canadian cases discussed above that the extinguishment rules deliver title where the seller does not have title, or has impaired title. The above United States and Canadian cases dealt with situations where the seller has good title, but the goods cannot be transferred to the buyer yet given they are unfinished (unascertained), or mixed with bulk.

Why do most extinguishment rules apply to extinguish any security interests if nemo dat still applies to the sale or lease transaction?

The position is not clear but the better interpretation of why most of the extinguishment rules apply to extinguish security interests granted by anyone (not merely the immediate seller or lessor) is that security interests granted by previous owners may remain unextinguished over collateral. If a buyer or lessee otherwise comes within an extinguishment rule, it would be unfair for a historical secured party who holds a security interest granted by a previous owner and which remains unextinguished, to be able to assert that security interest against a current buyer or lessee.

Nemo dat is partially overridden in relation to the priority of title-based security interests

One area where the PPSA clearly does override the nemo dat principle emerges upon the enforcement of security interests. Security interests that rank ahead of title-based security interests such as leases, consignments and retention of title sales, allow the secured party or any controller appointed by them to sell the title to leased, retention of title or consigned collateral. It does not matter that the grantor does not actually own the leased, retention of title or consigned collateral. This is because leases, retention of title sales and consignments (and any other title-based security interests for that matter) are read-down by the PPSA to be mere security interests. It is priority that is paramount among security interests, not title, upon the enforcement of security.

The New Zealand case of Graham v Portacom New Zealand Ltd (High Court) [2004] 2 NZLR 528 confirms that where a lessor of goods has not registered its lease as a security interest, a receiver appointed under a registered fixed and floating charge (general security interest) can sell the leased goods even though the lessee company in receivership does not own the goods. This is because:

(a) the PPSA treats a lease as a mere security interest, just like a general security interest;

(b) a mere security interest such as a general security interest can attach to leased property even though the grantor (the lessee) does not own the leased property10; and

(c) the matter is then resolved by the priority of the security interests. A registered (perfected) general security interest will defeat an unregistered (unperfected) lease.

In Australia (but not in New Zealand) most unperfected leases that secure obligations would vest in the grantor upon the bankruptcy, administration or liquidation of the grantor, so the question of a priority contest involving an unperfected lease upon the insolvency of the grantor would seldom arise. The leased collateral would fall back to the grantor’s estate and could be swept up by registered all- assets security interests such as fixed and floating charges and their equivalents under the PPSA in general security interests.

To state the obvious, a new secured party will not get the benefit of the extinguishment rules to extinguish a prior security interest in favour of its new security interest in collateral, even if the secured party extends new value (a further loan) to the grantor11. Only buyers or lessees can benefit from the extinguishment rules.

Lessees and the extinguishment rules/new security

Another related point to the nemo dat issues discussed above is whether lessees of collateral, or others merely in possession of collateral without title, such as lessees and buyers under retention of title sales, can grant further security interests in collateral (as opposed to sell collateral), other than over their leasehold or possessory interest.

A lease may be a security interest, but the lessee has not actually granted any interest in the collateral as such (other than by force of the PPSA). Under the (non-PPSA) general law it is the other way round - the owner or lessor of collateral has granted a leasehold interest to a lessee. The PPSA then regulates a lease as a security interest.

It is not clear but the weight of views appears to be that a lessee or other bailee of collateral does have sufficient interest in the collateral to grant a further security interest in the collateral. Naturally a grantor with a "possessory" interest (a lessee) could grant a further "possessory" security interest (a sublease). The question is whether the PPSA goes further and permits a "possessory" security interest holder (lessee) even to grant a mortgage or a charge? It is not clear but the weight of views appears to say yes. Again, this is said to arise from the "scheme" of the PPSA as opposed to any particular provision of the PPSA.

If a lessee or other person in due possession of a motor vehicle without ownership of it manages validly to sell or lease (by private sale or lease) the motor vehicle and pass good title or interest (because an exception to nemo dat applies), then the extinguishment rule in section 45(2) may apply to extinguish security interests over the motor vehicle. The extinguishment rule in section 45(2) is the only extinguishment rule that (on its express terms) applies where the owner has lost the right to possession, presumably because the motor vehicle is leased to another.

What does “extinguish” mean in relation to leases?

What is the position of a secured party if a lessee (not a buyer) takes free of a security interest under an extinguishment rule (the extinguishment rules apply to both sales and leases), but then the lease term expires and the collateral is returned to the lessor/grantor?

Leases are by definition for a limited period, and upon expiry the collateral reverts to the grantor free of the lease. For goods only, upon the expiry of leases, security interests that were extinguished by the lease re-attach to the collateral12.

Perfection of the extinguished security interest(s) re- enlivens, and priority is determined as if the goods

were never leased and the security interest was never extinguished13, provided that a registration of the security interest that was extinguished remains effective when the lease expires and the goods return to the lessor/grantor.

Knowledge – knowledge of security interests, or that the sale or lease of collateral breaches the terms of the security agreement under which the security interest to be extinguished arose

It is a condition to the operation of the majority of the extinguishment rules that the buyer or lessee must

have no actual or constructive knowledge (although sometimes it is only actual knowledge) that the terms of the security agreement under which the security interest to be extinguished arose, may have prohibited the sale or lease transaction. Security agreements will often include restrictive (negative pledge) covenants that prohibit the grantor from selling or leasing collateral without the prior consent of the secured party. Where security agreements include these covenants, and a buyer or lessee knows that the sale or lease transaction by which they will take the collateral breaches the security agreement terms, the security interest will not be extinguished where this condition applies to an extinguishment rule.

This is a powerful reason always to include appropriate restrictive covenants in security agreements to prohibit the sale or lease of collateral without the prior consent of the secured party. Practically, the terms of security agreements will not appear on the PPS Register. A limited class of interested parties, such as other secured parties and auditors, can obtain copies of security agreements.

It seems unlikely that many cases will arise where an extinguishment rule does not operate because the buyer or lessee has knowledge that the sale or lease transaction breaches the terms of a security agreement to which the collateral is subject.

Further, the extent of knowledge varies. Sometimes the knowledge requirement is actual knowledge, sometimes actual or constructive knowledge.

More confusing still is that sometimes the knowledge requirement is knowledge that the terms of a security agreement are breached by the sale or lease (as described above), and other times it is mere knowledge of the existence of a security interest over the collateral. Clearly, a requirement of mere knowledge of the existence of a security interest is favourable to secured parties because buyers or lessees may know of the existence of security interests if they search the PPS Register (assuming perfection is by registration).

Notes:

1 Sale of Goods Act 1895 (WA), section 22

2 Goods Act 1958 (Vic) section 30, and equivalent provisions in other Australian States.

3 See for example Re Anderson's Engineering Ltd [2008] B.C.W.L.D. 528. Re Anderson was a dispute between the holder of a registered all-assets security interest over the assets of a company which manufactured fire trucks, and a finance company that financed the fire trucks by acquiring title to components used to manufacture the trucks and leasing the components back to the company.

4 [1987] 1 W.W.R. 545, Saskatchewan Court of Appeal (Hall, Vancise and Gerwing JJA).

5 See paragraphs 16 to 18 of the judgment.

6 [2002] B.C.W.L.D. 528, British Columbia Supreme Court (Wong J).

7 See paragraph 34 of the judgement

8 Paragraph 11 of the judgment.

10 PPSA section 19(5), albeit only in relation to goods.

11 PPSA section 42(b)

12 PPSA section 37

13 PPSA section 37